The Infinite Well of Capitalistic Wanting and the False Promise of Manifestation

Trauma responses and Embracing Stability

I have now lived in my new apartment for almost two months. In early July my landlord illegally terminated my lease, and I had to scramble to find a new place. Everything aligned. I moved. Now I’m here. The rent is at the very top of my range, if not above it, but now I don’t have to spend money sealing cracks and doing pest control on my own (there are so many bugs in Florida). The apartment is almost a thousand square feet. I’ve never lived in a place where, if something needs fixing, I only have to file a maintenance request. They replaced my broken window two weeks ago and I still can’t believe it.

My bedroom still feels empty because I don’t have very many things. There’s a huge closet leading into the bathroom. And a bathroom closet, plus the closet in the hallway. From the small hallway I can walk into the living room (also huge) and see the dining room with my secondhand Ikea table and craft supplies, and the kitchen. Then there’s another closet near the front door. I don’t know what to do with so many closets; I resist the urge to fill them.

My little loveseat sits in front of an electric fireplace(!) and my very small television occupies the mantel, flanked by pothos plants. The kitchen has a dishwasher and a(nother) small closet with a washer and dryer. From my living room I can open a door onto my balcony, which overlooks lush greenery— several kudzu-covered trees and, beyond those, a whispering collection of pines and oaks. A stream gurgles below. Birds flit to and from me neighbor’s bird feeder. I’m growing arugula and lemon balm and peas on my balcony.

At night a green tree frog crouches beneath my porch light; a little bug hunter waiting for dinner. Sometimes there’s several, all lit up by the bulb’s golden glow. The cicadas were singing their late summer songs up until a week ago, when the nights cooled; now I leave the windows open in the evening instead of using the air conditioning.

All the stuff that filled my tiny cottage to the brim makes this place like a minimalist’s domain. It’s wonderful.

Because my PhD program pays so little, I take out student loans each semester.

Part of me hopes that, once my book comes out, I may not have to do this anymore; I hope to start paying the loans back before I graduate. Another part of me believes this is only temporary. There have been several times in my life when I’ve felt some semblance of financial solid ground, but never for longer than a year or two. I have credit card debt; loan debt. Expensive car insurance and pet insurance and health insurance and my monthly car payment. But I’m not accruing more credit card debt, and I’m paying my monthly balances. If I’m responsible with my money, I’ll be able to pay them off within a couple years.

I used to think that I wanted to be rich. I imagined a big Victorian house with a wraparound porch; a library; a sitting room and a giant kitchen. Or a modern place with gleaming stone countertops and big picture windows looking out at the ocean.

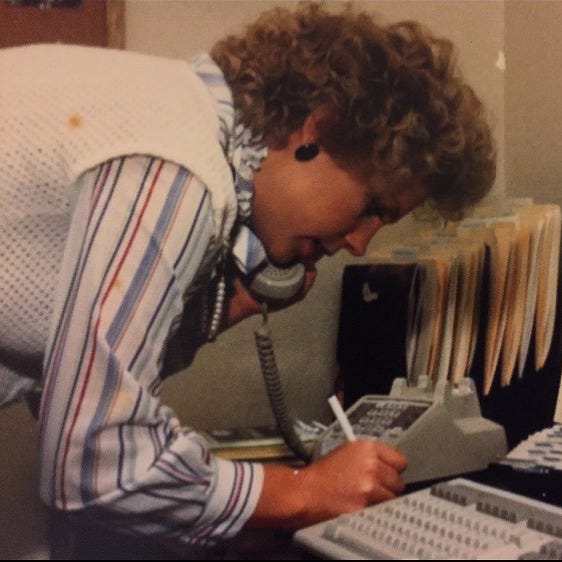

That’s what my mom wanted: Wealth.

She was twenty when I was born; a member of the Church of Scientology, but she left the church and Los Angeles and my dad before I was two. We lived in a basement room at first. One of her friends recalled coming over once for dinner, only to realize we were surviving on canned baked beans and powdered mashed potatoes. I still remember that place and its popcorn ceiling, the men my mom brought over, their late night sessions listening to records while I lay awake in bed watching the ceiling contort itself into shadowy shapes and figures in tune with the music. We moved often. I became a pro at answering the phone— she never did. It was almost always debt collectors. “I’m sorry, she’s not available,” I’d say, watching my mom flail her arms and shake her head at me. I learned how to sound like an adult, how to smooth out my voice like my mother did whenever we left the house.

I always thought we were poor, because my mom said we were. Our utilities got shut off. Sometimes we couldn’t afford groceries. I wore flappy shoes and stretch pants. Big t-shirts. I always smelled of cigarette smoke.

One day we went to my grandparent’s house, when I was about seven, and said we were moving in with them. She brought several trash bags filled with my things into her old bedroom. Then she disappeared for two years.

I saw myself as a financial and emotional burden. In her rages she told me how I held her back and what her life could be if she didn’t have to take care of me. She always got a migraine when we went shopping for school clothes, or cramps. I learned not to ask for anything I wanted; to let her choose it all. I learned to watch her face and body, alert for any signs of discontent.

The thing was, we weren’t poor. My mom made about $35k a year, sometimes more, and this was in the 1980s. That’s my yearly income now, in 2024.

The thing was, we weren’t poor. My mom made about $35k a year, sometimes more, and this was in the 1980s. That’s my yearly income now, in 2024.

We weren’t poor, but my mom’s obsession with wealth made us poor.

For my clothes we shopped at Value Village, a thrift store, or JC Penney’s. But she bought her clothes at Nordstrom and The Bon Marché, a now defunct department store with a high price point. Her closet was filled with jewel-colored dresses and crisp office attire. Lancóme and Elizabeth Arden eyeshadows, lotions, and foundations perched precariously on the edges of our bathroom sink. She spritzed herself with drugstore perfumes, like Charlie, but also with Annick Goutal. She drank. A lot. And went out with her friends many nights a week. Because of her spending we sometimes went without dinner. I learned to make Top Ramen with an egg and canned peas. Hamburger Helper without the hamburger. She couldn’t stop herself from buying nice things. It was a compulsion.

Sometimes I asked if we could go on welfare. Many of my friends were on welfare, and they seemed more financially stable than us. Well fed, at least. She said she didn’t want government money. In reality she made too much money to qualify.

This sounds very judgemental, I know.

Being a single mom, especially in the 80s (but also now), is incredibly difficult. My mom grew up poor— her mother worked as a night nurse and her father was unemployed; too traumatized from Marine deployments. He’d fought in two overseas wars. She had three siblings, and my mom told me about their childhood; how lucky I was that she wasn’t an addict like my grandmother, who was hooked on the opiates she stole from work. According to my mother, my father’s absence was a boon. He was, she said, a sociopath; a deadbeat who rarely paid child’s support. Sometimes he came around and took me for a day. Sometimes he called and we made plans. I’d wait for hours, sitting near a window and watching for his Cadillac until it got dark. Still, I always believed him when he promised to show.

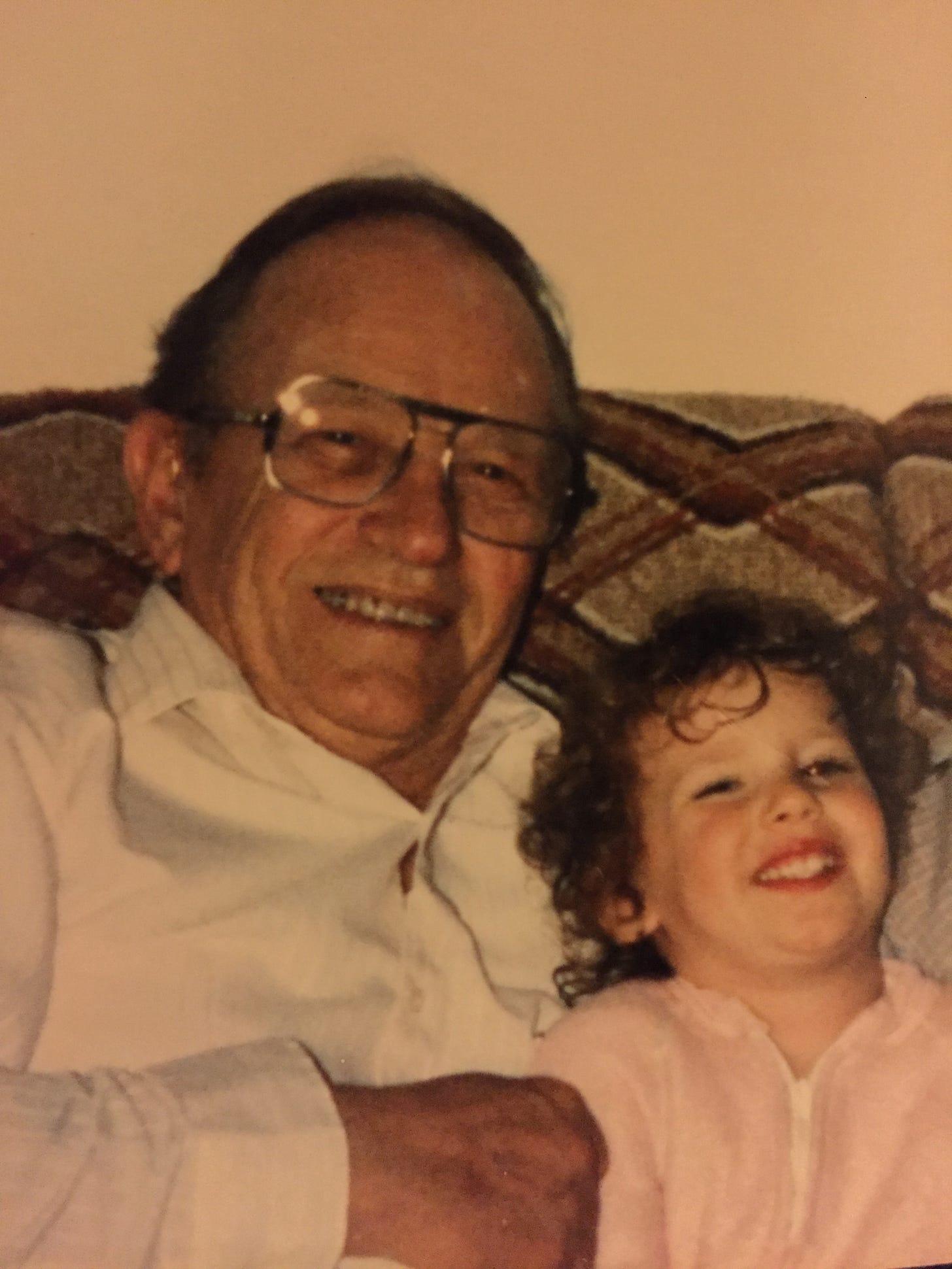

By the time my mom left me at my grandparent’s house they were different people. My grandfather was sometimes grumpy but mostly kind. Some mornings he tap danced in his slippers for me; on weekends we went to a local Buddhist temple together, where the nuns fed all the kids ice cream. He was a pro whistler. My grandmother was a raspy-voiced chain smoker but also an addict, sneaking Listerine in the bathroom and constantly taking laxatives because of the opiates she still hoarded. But she wasn’t mean. I loved hugging her, smelling the Listerine and baby powder and tobacco and being enveloped in the soft folds of her body. She cooked full meals a few times a week: fried chicken and apple pie and meatloaf. In the evenings I’d eat vanilla ice cream with my grandfather, the television at full volume because he refused to turn his hearing aids up high enough to hear.

Sometimes I went to AA meetings with her, where I’d sit in the corner, coloring and listening to the stories everyone told. Her addiction mostly flew under my radar. I thought she was on a lot of medications, and never questions the drawers filled with orange pill bottles, many of prescribed to people I’d never met. I liked their rattling and examined the multicolored pills, foreshadowing my own addiction to pills and opiates.

I made sure not to be a burden to them. I had already, by then, learned to be invisible. To become whoever I thought people needed me to be.

When my mom died by suicide in 2010, she left a note saying she had run out of money.

She was single again, after having been married to my stepfather from 1993 to 2007. He came from money. They had started a project management business in 1994 and made, I think, millions of dollars, though I really have no clue how much it was.

When they married, we all moved into a big house in a Seattle suburb— my first house, other than the tiny one I’d shared with my grandparents. They left me there for a week while they drove to Texas to collect his things. I ran away for the second time, and only returned after they did.

I was 13 and filled with rage. Rage from the abuse and neglect I’d endured growing up, and rage from the abuse that continued in new forms. My stepdad was the enforcer. My mom was done dealing with me. I ran away constantly. An easy scapegoat; a fluttering canary in the coal mine. They drank and fought.

The money shielded us from so much. Right before they married, CPS had been investigating my mom for child abuse, but the case was dropped soon after the marriage. When my stepdad abused me and I reported it, my mother threatened to disown me and charmed the social workers with her warm and welcoming smile. I told them I’d lied, terrified of losing the only family I had.

My mom was done dealing with me. I ran away constantly and became the scapegoat of our trio. They drank. And fought. The money shielded us from so much. Right before they married CPS had been investigating my mom for child abuse, but the case was dropped soon after the marriage. When my stepdad abused me and I reported it, my mother threatened to disown me and charmed the social workers with her warm and welcoming smile. I told them I’d lied, terrified of losing the only family I had.

My mom’s family loved my stepdad because he paid all of my mom’s debts and transformed our lives financially. His parents were good people; stable and quiet. We visited them in Texas for Christmases.

Behind closed doors it was chaos. Loud, violent fights every night after I went to bed. When I began misbehaving, refusing to call my stepfather “dad” like they demanded, they installed a lock on my bedroom door, so they could lock me inside. My mom would sometimes pin me to the floor, overcome with rage at something I’d said or done. My stepfather taunted me. You think you’re so smart. He was sarcastic and cruel. But we had enough food to eat. Few people believed me when I tried to tell them what it was like living with them.

My perception of money has, for a long time, been distorted.

I started babysitting when I was eleven, and got my first “real” job when I was sixteen, working at the front desk of a chiropractor’s office. I wrote checks at the grocery store. This was when you could write a check for more than the balance amount and the cashier would give you cash. I overdrew my new bank account, and my mom and stepdad sat me down for a talk. You can’t do that. But that was how I’d learned to spend money. I’d watched my mom do it for over a decade.

As an adult I always held several jobs but, in my late teens and early twenties, spent my money on drugs and alcohol. Sometimes I sold drugs. I worked as a stripper; as a sex worker. I took odd housekeeping jobs and frequented Labor Ready.

Whenever I had enough money I spent it as quickly as I could. I was scared of having enough. Scared of what money could do to me, or turn me into.

At 19 I started working as a wildland firefighter, then took a job two years later as a hotshot, working on an elite wildland firefighting crew. I ended each season with a fat balance in my checking account and lived as if I were rich; as if money came easily, until it was gone. Still, I didn’t open a credit card until my early thirties. The thought of a mortgage or a car payment or debt provoked panic in me. When I put myself through undergrad in my early thirties I lived on $40 a week until I found a good nanny job, then I bought myself nice boots and perfume instead of saving anything.

Now I do have credit card debt. Not a ton, but enough. And the student loans. My income has taken a hit because of how much work I put into my book over the past six years. My advance was $50k. That’s less than $10k a year for the time I spent writing and revising. Ultimately I was paid much less than minimum wage for that work. I’m still waiting for the last portion of my advance.

But if that works pays off— if I earn out my advance by a large margin, it could transform my life.

Only if I let it.

Which means letting go of this fear of not having enough.

Strangely, the fear of not having enough has historically led me to buy more. This was part of my inheritance— the spending. The cycle of enough and not enough.

When my mom and stepdad divorced she got a $500k settlement.

At first she had plans; dreams of opening a bookstore or buying a house. But it took her less than three years to spend half a million dollars: on wine, trips to Costco, gifts for her younger boyfriend, luxury skincare and hair care and perfume and expensive antiques and a rental home in a wealthy Seattle neighborhood, way above her price range.

When she died, I paged through her notebooks; mostly lists of the things she wanted to manifest. A Porsche. A villa in Italy. A wealthy husband.

In those pre and post-divorce years she’d become obsessed with a book called The Law of Attraction. Brainwashed, really. Whenever I was too negative she corrected me. I can only imagine what it was like inside her head— she must have been constantly policing herself, fearing the low vibration frequency the book warned against.

She believed that the money she spent would attract more money. Even after she got laid off from her high paying project management job, she kept spending, until her basement was full of boxes filled with antiques and expensive home appliances. Until her unemployment ran out.

She believed that the money she spent would attract more money. Even after she got laid off from her high paying project management job, she kept spending, until her basement was full of boxes filled with antiques and expensive home appliances. Until her unemployment ran out.

That’s what I inherited. Plus the $2,000 she left me in cash, in an envelope. She didn’t leave a will or any hint of what I should do with her things, or what they meant to her.

Over the course of several years I sold and gave away everything my mom had left behind, excepting maybe ten small items, and some pictures. I had a garage sale and sold her Limoges figurines and expensive antiques for cheap. The money from her Lexus bought me some space to grieve, because nannying, my most lucrative skill, was too challenging in the wake of her suicide. Everything was challenging. On most days I set a goal for myself: stay alive for the whole day. The next day will be different.

I have, at times, regretted how I handled my inheritance. Couldn’t I have sold those things on eBay? Made more money from them? Invested the money from the sale of her car? A family friend told me, at one point, to talk to a financial advisor, but I had no concept of what that meant. I couldn’t imagine myself as someone who saw a financial advisor. Besides, I was broke. Living in Seattle was expensive. I paid out of pocket for my community college classes. I moved to California. Then, when I got accepted at Syracuse, I drove across the country in my beat up Honda Civic and took a job as a hotel housekeeper for a couple months before school started. I made about $500 every two weeks.

I don’t regret any of it now. I don’t regret using that money so I could work part-time instead of full-time, or paying out of pocket for my therapist. I don’t regret getting rid of her stuff as fast as I could, because my intuition told me it was somehow soiled. That her spirit lingered. I had unpacked all of her boxes, unwrapping antiques until my fingers were stained black with newsprint; reading boxes of letters and memorabilia. I didn’t yet know that I was dissociating.

I missed her so much, but I was scared of her, too. Her, and the grief itself.

A few months after my mom’s suicide a therapist told me her spirit was trying to possess me.

The therapist said it was a destructive force. That I shouldn’t be driving my mom’s car around. According to her, I needed to create a protective orb around myself; a tunnel to and from the doorstep of my home. Although this was deeply traumatizing (I found a better therapist, who I still see), she wasn’t totally wrong. I felt it. My mother was haunting me.

Her suicide was deeply complicated— a progression of events. I had set a boundary and taken space from her, and shortly after this she told me she had cancer. I moved from Denver to Seattle, to try and take care of her. But she wouldn’t see any doctors, and it became clear, though I couldn’t fully admit it at the time, that something sinister was happening. After her death, she left a note admitting that the cancer wasn’t real. She had lied about it.

It’s taken me over a decade to reckon with my mother’s intense need to control me. I was a vessel she filled with rage and hatred. I turned the rage and hatred inward. for her, I felt a deep sense of compassion and obligation, as if I were personally responsibility for her well being. She was sick, in so many ways. I had spent my whole life trying to make her happy.

Choosing to live in a nice apartment was not a trivial decision for me.

Deciding that I deserve to live somewhere safe instead of trying to find the cheapest place to live, as I always had, feels transformative. It’s worth the student loans. Since living here I’ve felt less scarcity, despite the rent being more than I am used to. I put six month’s rent into a high yield savings account that I don’t touch, and now that I’m not using credit cards anymore I have to be realistic about what I can afford.

A month ago, fourteen and a half years after my mom’s suicide, I realized that it’s time for me to draw the boundary again. The boundary that I couldn’t hold before.

I hadn’t realized how much guilt I was carrying— how, although she has been gone for so long, I still felt responsible for her. In seven years I’ll be 51, the age she was when she killed herself. Every day I feel privileged to be alive.

Closing the door on her spirit, and what she passed on to me, is not a willful ignoring of what I have learned from her.

My mom taught me who I want to be, and her death taught me who I am not. I was always so scared of being like her, but in many ways I am her opposite.

After I gave away all of her things there was a part of her still inside me: that part longed for symbolic possessions, like the Le Creuset cookware and fancy perfumes and nice appliances. Shiny things that made me feel like I had some sort of status.

That part is gone now. I have no aspirations of wealth. I don’t want to visualize myself in a beautiful coastal house, or imagine a life of riches in order to attract abundance. Because abundance? Abundance is having enough to meet my basic needs. Abundance is having the time to write. Abundance is relational. Abundance is giving myself the gift of space. Abundance is reaching out to others and being in nature and opening myself up to what has always felt the most terrifying: human connection.

There are, of course, things I want. Like a nice place to live. I have that now.

Would I love to own a little plot of land and have a garden and maybe some goats and chickens? Yes. That is something I would love. But the world is a tenuous place. Nothing is guaranteed. It seems like the most fruitful endeavor is to cultivate gratitude for what I have now, and a mindfulness regarding my habits of consumption. To be conscious of what I want and why I want it. So my wanting doesn’t consume me.

I have the wildest dreams for success, but I am careful about how I define success for myself.

I dream that my book will be successful. That my story will reach people. Success is connection. Success is having enough stability and funds to keep writing. All I want is enough. Not more than that. And if the universe gives me more, I want to be able to accept it, with gratitude, instead of fearing that it will disappear, and needing to hoard it in some way or another. I want to share it.

We live in a culture that tells us money is the most important thing.

I have lived through enough to know that money is, indeed, important. Money can buy happiness, especially if you have been struggling for so long simply to survive. But beyond our basic needs, money is meaningless. I have friends who make six figures, whose debt is worse than my own. They live paycheck to paycheck and feel as much, if not more, scarcity than I do.

I have worked as a nanny for millionaires with home gyms and theaters, who still feel as if money is scarce and have little time to spend with their children. There is always something more to want, no matter how much we have.

Money buys happiness, but it cannot sustain happiness.

We do that for ourselves.

Thank you so much for reading. I am deeply grateful for your time and attention.

Join me for a writing session tomorrow from 10am-12pm: open to all paying members of Navel Gazing!

Access the Zoom link here:

Money is so complicated whew! I grew up with money—as in, my mom's parents were rich thanks to a business they opened after their three kids were adults, my parents ran a tennis academy and were terrible at managing their money and decidedly not rich, but my grandparents helped us financially. My grandparents were first generation Jewish immigrants who bootstrapped their way into the "American dream" but what that meant was that money was kind of all they cared about. Any partner I've ever had has been judged by how much income they made. They expressed disappointment when I went into social work because of the salary the job comes with. Their financial support always came with strings—when I went through a brutal custody case and almost lost my children, no one offered me money for a lawyer because I was queer and divorced and they didn't approve of those things. My ex-husband financially ruined me and managed to steal almost all of my generational wealth, including the two-family home I'd purchased for us when we got married.

I'm comfortable financially now but only because I married someone with family money. I make only like $30,000 a year. We recently bought a house together (read: he bought us a house) and for a while we were looking at all these historic, beautiful Victorian homes and I got so caught up in the idea of living in one of them until we put an offer in on one that was accepted and I began to really look at the reality of the financial and physical upkeep of a house like that. I realized that I didn't want or need a huge house, I just wanted something comfortable and manageable. It's definitely going to be a lifetime of work to unlearn the messages I got about money (I'm also a 2H Leo, I like nice things!!!) while also grappling with the ways I was punished—by my ex, by my family—for being queer and trans and getting divorced, how tenuous financial stability can be for those of us on the margins.

Sorry for this rambling mess of a comment! This is something I've been thinking about a lot lately.

River, thank you so so so so much for writing this essay and sharing it with us. It’s an honor to learn what makes you, you. You touched on so many complex subjects (inheritance, manifestation BS, mother-daughter relationships, being raised by someone who struggles with mental health, etc…) and told your story in such a beautiful way.

Closet Tip: Turn a closet into a sanctuary. Whatever that means to you. The closet in my home office is painted dark purple, with tarot cards sitting on a white fluffy rug. This is where I go to meditate/cry/journal/feel. Having a place like this in my home has done wonders for my sanity. It’s a special treat to create a safe space like for myself, especially after growing up in such an unsafe way.

Hugs to you! 🫶🏽