My first book debuts in three months.

Actually, it’s not my first book.

Hotshot, a memoir six years in the making, is my second book. My first book was a novel called The Open Curtain. I also spent half a decade working on that book. Trashing drafts and revisions, changing first person to third person, incorporating the feedback of mentors, peers, and agents. The Open Curtain won the Orlin Capstone Award for best overall senior capstone at Syracuse University, and I took the novel with me into my MFA program (also at Syracuse), querying agents throughout my third year, experiencing the thrill of full manuscript requests only to field rejection after rejection– I’ll be cheering you on from the sidelines and I just don’t think I can sell this.

And it’s not like I was a twenty-something undergrad or grad student. Those rejections landed heavily in my late thirties. They felt so final. A rejection not only of the manuscript, but of me, the person. The writer. It didn’t help that my younger peers were successfully selling and publishing their books. I was thrilled for them, but I also wondered what I was lacking. Of course I assumed that I was lacking something, of course it had to do with me, with some sort of deficiency.

But it didn’t. It wasn’t about me at all.

The spring before I graduated from my MFA program, in 2018, I had lunch with one of my favorite mentors, who’d taught me as an undergraduate. She read my tarot cards and consoled me as I told her how hopeless I was feeling. I’m thirty-seven. I’ve worked so hard on this book. Why doesn’t anyone want to represent me?

It’s mysterious, she said. You never know how things are going to work out. But if you keep working, your time will come.

It’s mysterious. You never know how things are going to work out. But if you keep working, your time will come.

I’ve been having a hard time articulating things lately. Things like my feelings, my thoughts, my present moment experience. It feels like I’m holding my breath, waiting for August 12th, waiting to see how the world will receive my book, if it might transform my life in some way. Mostly, I want to have enough money. To be lifted above the poverty line, paying off debts rather than accruing them. Recently, my agent reminded me that 80% of authors never earn out their advance. I think he was trying to temper my expectations, and it worked. I spiraled into a dark, desolate place. After having poured six years of my life into this book the thought of not earning out my (nice but not huge) advance absolutely broke me.

Your time will come.

I sold Hotshot in May 2019, on proposal. To sell a book “on proposal” means that the editor bought the book without it having been written. My proposal was over sixty pages long.

I wrote it while nannying fifty hours a week in Seattle, waking at 5am on weekdays and staking out coffee shop spots on the weekends. The early winter mornings bled dark and damp, threading themselves across each day tighter and tighter until early afternoon turned black.

At the time, I was piecing together sublets and Airbnbs– my first sublet involved a sweet but absolutely deranged cat, hellbent on chewing off his tail. My only lifelines were the two babies, their kind parents, and my book proposal, potent with all my hopes for the future. An editor bought it quickly, in a Pre-Empt, and I accepted the offer while holding one of the babies on my hip.

Although I’d pinned all my hopes and dreams on this moment, it didn’t change me like I’d expected. For the first time in many years my bank account gave me a sense of stability rather than panic, but I was still me; working as a nanny, hopping dwellings. A few days after I signed the contract someone broke into my car and stole boxes of mementos, including childhood photos– worthless to the thief but invaluable to me.

Then I was offered a Fulbright ETAship in Czechia (after an extensive application process). After much thought, I accepted. In retrospect this wasn’t wise, but how could I turn down such an incredible opportunity? In the face of abundant opportunity I still feared future scarcity, so I said yes to everything.

I turned in the full draft a little over a year later, and waited. We were in Covid times. I had moved to Europe for a Fulbright, then left the Fulbright because of the pressure of my impending deadline, and come “home” to Seattle in March 2020. Sending in that first draft was a triumph. It was almost on time, and I’d sacrificed so much to make that happen. Then I waited. I took another full-time nanny job. Forgot about the book. I imagined that Hotshot would never be published. I waited, and tried to block out my anxieties.

Your time will come.

Ask any writer about their experiences publishing their debut, and each writer will give a different answer.

My path took over six years, and I never would have imagined it taking that long. There are two other wildland fire memoirs coming out this summer– both of those writers had their experiences of fighting fires and wrote their books in the same amount of time it took for my book to make it to publication, and both memoirs debut before my own. I predicted this two years ago, to a friend. I just know someone’s going to get there before me, but there’s nothing I can do. Still, with my last revision I asked for more time, because my health had deteriorated to the point of breakdown. It wasn’t the book’s fault, not completely, but turning around quick revisions while taking a full load of PhD coursework and teaching two classes per semester certainly wore me down. The whole process wore me down. The waiting. The pressure of revisions. But my experience was relatively typical.

In her most recent book, Memorial Days, author Geraldine Brooks writes about her husband, Tony Horwitz; a writer who, at age sixty, collapsed and died of a heart attack. She details the intense pressures they both faced when it came to book deadlines– quick turnarounds followed by long silences. At one point Horwitz relied on nicotene gum to keep him going– several packets a day. This reminded me of my last-ditch strategy for completing my last draft, copyedits, and proofs. Despite my declining health, I started smoking cigarettes. It was the first time in my life I was a regular smoker, and within months I craved cigarettes constantly.

I quit last December but slapped on nicotene patches in January in order to power through my last copyedits. Thankfully, I’ve been cigarette free for over five months. I’ll never pick one up again, but the strategy worked. With that extra stimulation I could pull off twelve or sixteen hour days– the only way I could reach my deadline.

I know this isn’t the case for all writers, but I think the burden often falls on writers whose work involves extensive research, whether for fiction, nonfiction, or poetry. Because of this, I’ve decided to write my next book in full, rather than writing and trying to sell a proposal. Either way, the publishing industry as a whole– editors, publicity folks, proofreaders and copyeditors and interns– they’re all doing their best, often for less pay than they deserve. Like writers, they do the work because they love it, and believe in the power of writing.

The other day I came across a hopeful, lovely social media post about wanting to become an author.

The messaging was something like I used to have no purpose but then I realized I was a writer, and now I know I am working towards being an author, and when I become an author everything will be amazing and my problems will be solved.

My immediate response?

Bitterness.

I observed my bitterness and reread the post. I’m sure I posted similar sentiments years ago on Twitter and Facebook, because I needed to believe in a pinnacle. Climb long enough and hard enough, and that’s it. You’re there, at the top.

An early mentor called me hungry. He said all writers needed to be hungry for something.

You’ll get there, he said, because you’re hungry. He was right, about the hunger (not so much about the there). My hunger came from a place deep inside me– from my child self, who longed to be seen and recognized and loved.

I once hungered for the life I have now, which means I didn’t know what I was hungry for.

In other words, the kind of hunger that propelled me to this moment is (and will remain) insatiable.

This is what I am learning.

My time has come.

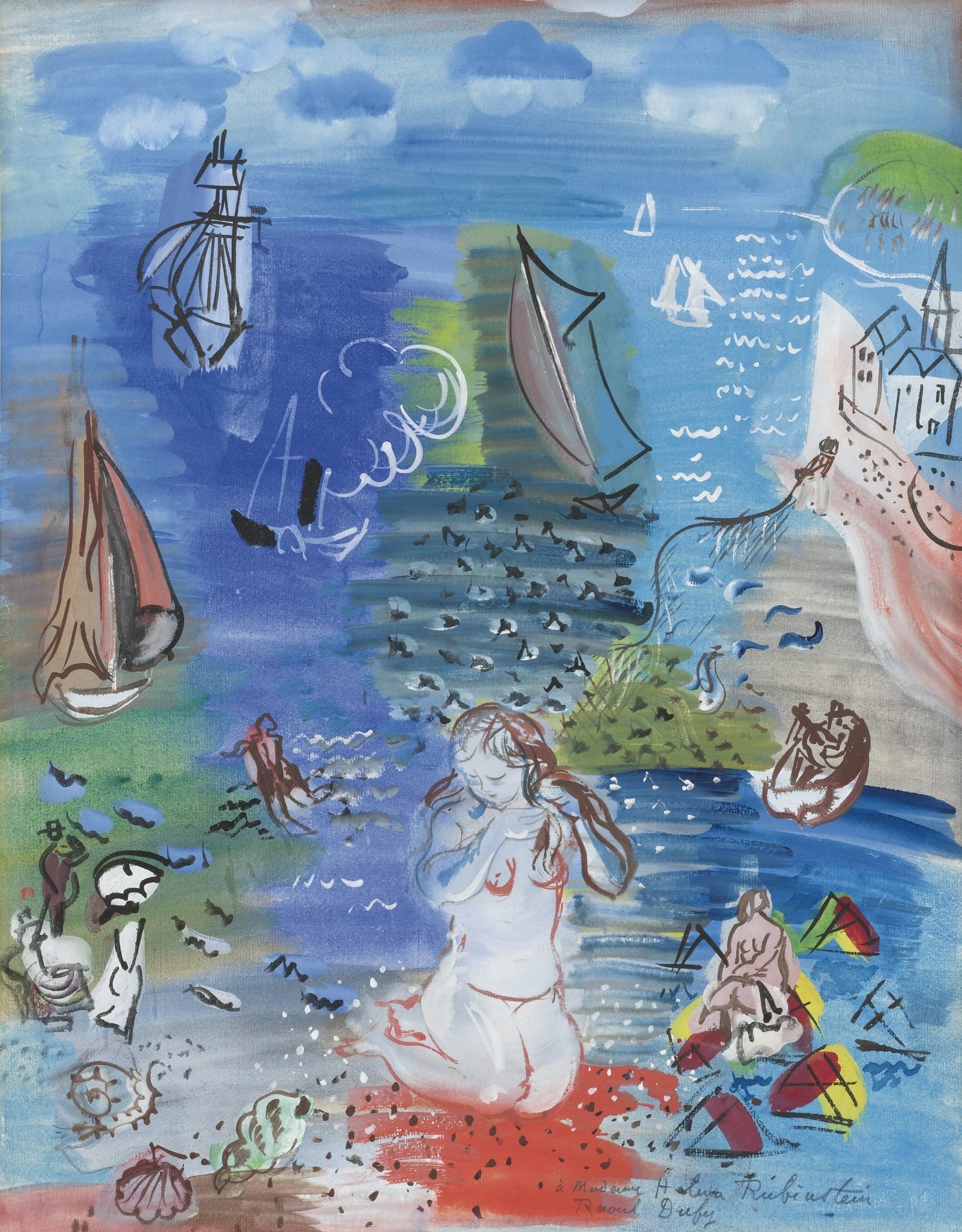

My sails shudder, the wind inconsistent and unreliable. They sing with each gust of praise, then sigh and wilt. I must learn to work with the unpredictable wind; staying tied to the mast when it’s strong and being invisible to the world when it dies down. Or maybe it’s best that I not see myself as the sails, or the boat itself, but as the sailor. I learned to sail only on rough waters, sprinting from one task to another, trying to stay afloat.

The glassy sheen of a calm ocean exposes me to myself, my image reversed and semi-distorted, as if to say wherever you go, there you are.

I gave up so much to make this book happen, and there’s no guarantee that it will have been worth it. No guarantee that people will like it, or read it, or that I’ll make a single dime beyond what I was already paid.

A sailboat can also be a rowboat.

Maybe I row, rest, and row. Maybe I turn my face upwards, towards the sun and clouds and rain, and feel it all.

What makes something worthy of our time and effort?

Here is where I always arrive.

Here, to the words of another mentor: Find your joy in the work itself.

Find your joy in the work itself.

Joy. In the work.

Or, as Mahatma Gandhi once said: The path is the goal.

I spent six years working on The Open Curtain, a book that will forever remain unread. It garnered me no money or accolades beyond the Capstone award.

Still, I remember the writing process itself as a space, not a thing.

Not an object.

The writing process is a space beyond the physical; an intellectual and spiritual and emotional playground in which I dance and swing and sometimes fall hard enough to draw blood.

That book was practice.

Hotshot is also practice. With The Open Curtain my practice space was bare bones. I seeded and planted and excavated parts of myself and my experience. I tried different methods of storytelling, donning voices like costumes. Everything I learned I carried with me into this book, and I spent six years in a room, mostly alone, creating this book from nothing. Or from everything. Or both.

Now that I’m really thinking about it, I see an alchemical process. I read hundreds of books and essays and journals and archival materials and absorbed them into my psyche until they emerged in my own words, synthesizing with my own life and experiences, until I couldn’t help but see the connections between my most painful and beautiful experiences and those painful and beautiful things that came before and after me.

I created something.

A book.

I fucking did that.

When it comes down to it– that was my dream this whole time. To create a book I am proud of and release it into the world, a fully formed animal with its own soul apart from mine.

My control stops there. I open the door and watch, and hope. But no matter what happens, it was worth it.

HOTSHOT’S FIRST REVIEW

Last week I learned that Kirkus Reviews gave Hotshot a Starred Review. Here’s what they had to say (read below or go to the review):

I cried. I definitely cried.

Next week I’m writing about the impacts of artificial intelligence– not on the environment, but on our brains and psyches.

I’m also cooking up a couple one-off classes/workshops for the summer. You’ll hear about those soon.

And if you’re going to be in New York City on August 15th, make sure to mark your calendar for my book release and reading, which will be at P&T Knitwear, on the Lower East Side. I’ll be accompanied by some lovely folks and would LOVE to see you there.

Tell me how you are? What you’re working on? What’s challenging or easy or anything in between? Sending love.

I requested my library to order your book and they said they will when it releases, so excited for you.

I feel this all so much, River. Similar arcs, similar hopes, similar disappointments, though of course with different life circumstances and challenges. (And, just to tell you you're also not alone in this, I decided to write my next book, too -- I have a proposal, and shopped it around after over a year of work on that monster, but I think when stories want to be born maybe sometimes we have to let them come out all squirmy and crying and figure out how to make them presentable afterward.)

Hotshot is preordered at my local bookstore! And also to tell you you're not alone -- my little group of science writer friends has two people who write about botany, and we've talked a lot about what it feels like to watch other books on your same subject come out at the same time. Consensus seems to be that if any one of the books does well (hopefully your own), it actually helps the others because people look for other books on the subject. Not that it makes it feel any better