Learning from Virginia Woolf's essay, "The Death of the Moth"

Writing is paying attention and guiding attention

I’m now offering a deeply discounted yearly rate for students, teachers, and anyone who doesn’t have the resources for a full-price subscription. Please don’t hesitate to respond to this email if you are unable to afford this discounted rate, and I will comp you a subscription. I want to keep access open, even to paywalled posts.

Note that this discount is specifically for folks who don’t have the resources for a paying subscription. If you can afford it, please consider becoming a paying subscriber (and thank you so much if you already are!)

Additionally, there’s a summer special until the end of June! Get 15% off for a one year subscription. This means you’ll pay $3.50 a month as a paying subscriber. Please consider subscribing and supporting this work.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the phrase “paying attention.”

The etymology of the word attention means to stretch toward. Its root, -ten (to stretch thin) lives in many words of many languages.

Attention.

Tension.

Tend (to incline, to move in a certain direction).

Tender (soft).

Pay can be interpreted many ways, but two of its most common meanings have to do with a) an exchange for goods, and b) to appease, or make peaceful.

The phrase pay attention was first recorded in the 1580s: it means “to ‘give or render’ with little or no sense of obligation.”

It is this kind of giving, or rendering, with little or no sense of obligation that I am most interested in.

The writing I treasure is a kind of paying attention. Writing as an art form guides the reader’s mind, and the reader’s mind reaches towards something. Stretches towards. The writers I treasure and admire tend to guide the reader’s attention without assuming anything about the reader except for their innate intelligence and potential to understand.

In “The Death of the Moth,” Virginia Woolf brings the reader’s attention to a moth. But she does not write: here is a moth. Here is what a moth is. A moth is constructed from these things, and means this. Here I am. Here is what I am feeling. This is the situation.

Instead, she suffuses what could otherwise be a mundane event (a moth flying around a room, tumbling onto a windowsill, and dying) with universal meaning, but also imbues the moment with her characteristic melancholy. As a writer, Woolf’s voice is distinctive and clear. She trusts her reader to accompany her on the journey.

In this short essay. Woolf’s writing breathes, and as it breathes it magnifies and dilates, again and again, all while paying the moth close attention, and paying close attention to each word and sentence, guiding the reader inside and outside (both physically and spiritually) towards a deeper understanding of life.

It’s also useful to notice the sentences themselves. Their structures and variability, which set the pacing of the essay. Below, I’ll conduct a close reading of the essay, which is my own kind of paying attention.

I encourage you to read the essay on your own first. It’s very short and you can read it here. After reading it, close your eyes and write down how you feel. Then come back here.

The essay begins:

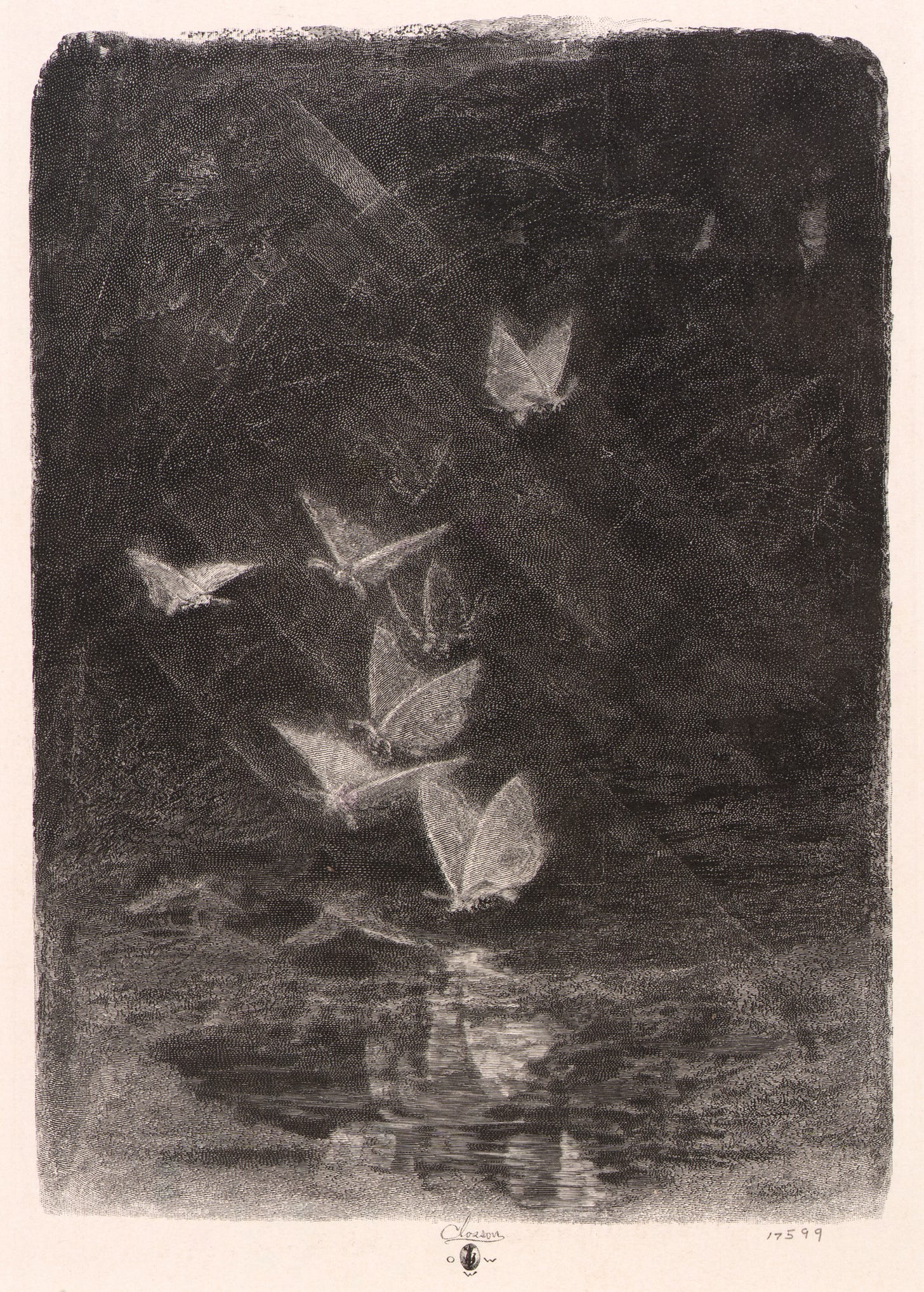

“Moths that fly by day are not properly to be called moths; they do not excite that pleasant sense of dark autumn nights and ivy-blossom which the commonest yellow-underwing asleep in the shadow of the curtain never fails to rouse in us. They are hybrid creatures, neither gay like butterflies nor sombre like their own species.”

Here, in her first two (two!) sentences, she opens the essay with the general, defining moths for her reader as she perceives them but also creating a liminal space. The moth, transformed by daylight, is not itself, and neither is the world of the essay. Woolf traces an outline of this new creature, not quite redefining it, and leaves her reader in a translucent, almost otherworldly space of unknowing. Then she colors in the sketch, bringing the moth alive for the reader before opening up the physical space of the essay to include her view outside:

“Nevertheless the present specimen, with his narrow hay-coloured wings, fringed with a tassel of the same colour, seemed to be content with life. It was a pleasant morning, mid-September, mild, benignant, yet with a keener breath than that of the summer months. The plough was already scoring the field opposite the window, and where the share had been, the earth was pressed flat and gleamed with moisture. Such vigour came rolling in from the fields and the down beyond that it was difficult to keep the eyes strictly turned upon the book.”

There is energy here. The moth seems content (seems, instead of is, creates an opening for interpretation). “Rolling in from the fields” is an energy so vibrant and vital that she can barely focus on her book (oh, for a window view to be the thing that distracts me!). You can see how Woolf is guiding the reader’s attention to the moth, out the window, and back inside to the book.

“The same energy which inspired the rooks, the ploughmen, the horses, and even, it seemed, the lean bare-backed downs, sent the moth fluttering from side to side of his square of the window-pane. One could not help watching him. One was, indeed, conscious of a queer feeling of pity for him. The possibilities of pleasure seemed that morning so enormous and so various that to have only a moth's part in life, and a day moth's at that, appeared a hard fate, and his zest in enjoying his meagre opportunities to the full, pathetic. He flew vigorously to one corner of his compartment, and, after waiting there a second, flew across to the other. What remained for him but to fly to a third corner and then to a fourth? That was all he could do, in spite of the size of the downs, the width of the sky, the far-off smoke of houses, and the romantic voice, now and then, of a steamer out at sea.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Gathering to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.