Ketamine Dreams: How the Hero's Journey Can Hinder Recovery

Plus: join us for Spacious Centering!

This essay details drug use, death, suicidal ideation, and recovery.

Don’t want to subscribe to navel gazing via Substack? You can subscribe or buy me a coffee via ko-fi.

We’ll have our first Spacious Centering mapping session for paying subscribers, live via Zoom on Sunday, January 28th at 5pm EST. The Zoom link to register and join is below the paywall at the bottom of this email. Spacious Centering Mapping is a holistic and exploratory space for generating ideas, increasing self-knowledge, and clearing clogged creative pathways via the use of images, intuition, and self-inquiry. You do not have to share anything in this session. It’s guided by me and doesn’t involve social interaction beyond introductions. Come with an open and contemplative heart. The session will be recorded and sent to all paying subscribers, whether or not you attend live, and all paying subscribers will receive PDFs with monthly practices.

I first used ketamine when I was nineteen years-old.

This was during the winter of 1999/2000, the second darkest winter of my life, and I was living in Eugene, Oregon, one of the darkest winter places, where layers of dense clouds sink low in the sky and the sun becomes a distant memory. Back then no one was talking about ketamine except for drug dealers, and one of my closest friends was a drug dealer.

I call him Peter now. That wasn’t his real name. He was five years older than me, but I’d been using drugs longer than him; since I was twelve. By the time we met (through a community college English class), I’d attempted and failed at sobriety more than once. Each time I relapsed, things got worse. Substances were part of my brain development beginning at twelve years-old. At thirteen I inhaled solvents, lines of cocaine and methamphetamine, and began sleeping with older men. By fifteen I was using ecstacy and LSD, and at sixteen I spent my entire sophomore year selling LSD, which I used nearly every day. The first time I shot up heroin I was seventeen. Or was I sixteen? It doesn’t matter, does it?

Unlike me, Peter was a purist. He preferred pills and never used needles. Went for mushrooms instead of LSD and took amphetamine but only in pill form. He especially liked pharmacological deep cuts, like ketamine and DMT. I understand his reasoning: heroin was no more dangerous than liquid morphine but shooting up was stigmatized. Any addict can create a framework justifying their addiction. Peter’s was intellectual. Me? I didn’t bother with a framework. I was all in.

This was the winter high-dosage Oxycontin was released on the market, and the giant pills, deadly for anyone without a tolerance, sold for $40 a pop. Sometimes Peter gave me a few for free. Each pill lasted a few days. I nibbled at them throughout the day. Sometimes this method failed and I’d end up sweating and clammy, trembling on the bathroom floor and waiting to throw up, or die.

Some people say that addiction functions the same for everyone. I think addiction is as individual as a fingerprint. Everyone uses for their own reasons, and not all addictions involve substances. Everyone is susceptible to addictive behavior, but those of us who grew up in abusive or neglectful environments often develop survival strategies to keep ourselves alive.

So much of it has to do with one’s childhood, but childhood isn’t always part of the equation. For me it was. I grew up in a chaotic, abusive environment and was often left alone for days at a time. My parents were unpredictable, each in different ways— my mother’s moods, absences, and drinking, and my father’s absence, promises and failures to appear, and his rare appearances.

Children’s brains and bodies prioritize trusting their caregivers. If a caregiver is unsafe, children unconsciously delude themselves into trusting them. Otherwise they’re like a baby bird fallen from its nest. The brain and body suppresses emotions, internalizes fear and anger, self-blames, and dissociates. Any childhood is normal to a child.

Many abused children grow up thinking the abuse is normal. Some never learn that it wasn’t. Others, like those privileged enough to access therapy, have to unbrainwash themselves as much as possible. But no childhood can be erased and colored differently. There’s always a residue.

As a child I learned to soothe myself with food; an activity with a high level of shame. I wrote about this in

‘s newsletter, The Unpublishable.By the time I was nineteen, when I met Peter, I was an open wound, constantly gushing blood.

What does a well-adapted person do when they have an open wound? I’d imagine they look for bandages so they can heal themselves and be whole again.

Being a whole, integrated person was never part of my experience. The wound was all I knew, so I kept it fresh.

The wound let me off the hook and freed me from responsibility. It kept me from being the person I wanted desperately to become: a writer, a college graduate. Someone with agency. The wound was a whirring engine inside my chest, propelling me towards pain. Pain was what I thought I deserved. Pain was familiar. Pain felt like home.

I slept with people who didn’t care about me and wished they cared about me. I lied about myself in the hopes that others would like me. I drank to blackout whenever I could afford the alcohol. I avoided intimacy and connection while longing for intimacy and connection. I threw up nearly everything I ate because I knew I didn’t deserve nourishment. What was nourishment? What was love? Anything real— anyone who wanted to help me or love me or saw my potential— terrified me. The thought of being exposed for who I was, which is what intimacy requires, felt like death.

Here’s the thing: when you grow up being told you’re a piece of shit, you really, really do believe that you’re a piece of shit. I was a broken mirror; separated into thousands of tiny shards all reflecting different images, trying to be whole.

Sometimes Peter gave me a few for free. Each pill lasted a few days. I nibbled at them throughout the day, trying to avoid taking too much at a time. When that happened I’d end up clammy and trembling on the bathroom floor, waiting to throw up so I could feel better.

I don’t know how people get ketamine now, but Peter got it in little vials, probably from some veterinarian hookup (ketamine is a horse tranquilizer). He’d cook down the liquid in a cast-iron frying pan, scrape up the solid crystallized layer, and mash it into powder. Its high price meant he used it selectively, almost ritualistically. Ketamine, he said, was a dissociative. It can give you a wide-lens view of your life. (This is one of the reasons it can be so helpful therapeutically).

The crystals stung like hell when I snorted them but they opened a tiny pinhole in the physical space of my sinuses. Pure light burst through the pinhole, casting everything gold. We laughed and laughed. My body disappeared— my cumbersome terribly body. Gone! Meaningless! All that mattered was my spirit! Spirits rejoiced and the world echoed an extended Hallelujah. It was a kind of joy I’d never experienced. The kind of joy children experience, except I couldn’t remember ever being happy as a child. Or being a child at all.

The high was formless and free of language. The comedown was nonexistent. Finally I believed in the potential for joy. Over the next few weeks winter melted away. Summer came. Peter and his roommate suggested I try wildland firefighting, so I did. In August I turned twenty. I was sober on that day, fighting fires in Nevada.

We laughed and laughed. My body disappeared— my cumbersome terribly body. Gone! Meaningless! All that mattered was my spirit! Spirits rejoiced and the world felt like an extended Hallelujah. It was a kind of joy I’d never experienced. The kind of joy children experience, except I couldn’t remember ever being happy as a child. Or being a child at all.

Then, winter came again.

In January 2001, Peter overdosed and died.

A week later his girlfriend Opal, me, and two other people drove to his hometown in Idaho for his funeral. We had two giant grocery bags full of pills, taken from his safe before the police arrived.

What I remember: the snow and the Percocet and driving icy mountain roads while thinking: I wouldn’t mind if I died. The motel. Opal and I clinging to one another in our shared bed. Loading ourselves up on benzodiazepines before the funeral. Walking the aisle to Peter’s open coffin. How alive he looked. Willing his chest to rise, and cupping my hand hard to my mouth in an effort to contain my sobs.

His brothers. His parents and the house he grew up in. The envelope of money his mother handed us, how it hung in the space between us all as the four of us shook our heads. We didn’t want to spend that money on drugs. But we did.

Peter’s parents told us all about him. In high-school he gave tours at the dam and got straight A’s. His mother brought out a tape recorder, pressing play until Peter’s child-voice filled the room, singing meow meow meow meow. The pinhole expanded deep in my heart, casting everything in shadows. I disintegrated.

That was the winter I wanted to die. I ate some mushrooms and took myself to a coastal cove. Peter’s spirit was there, all around me, and I cried. I could feel how peaceful he was. I could sense into other realms, so expansive. Why can’t I be with you? He had abandoned me in this beautiful, terrible place.

There are no pictures of me from back then, because I was barely a person.

When the pills ran out I started using heroin regularly, alternating with cocaine. Dirty spoons and needles littered my bedroom. I slept with people for drugs and money. My soul was an abyss, unfillable.

His brothers. His parents and the house he grew up in. The envelope of money they handed us, how we didn’t want to take it, knowing we’d spend their money on drugs.

Fire season came again, and without it I’d surely have died.

In early autumn, 2001, I took a nanny job in the Hudson Valley of New York. As a goodbye Opal invited me over for some ketamine— I’d graduated from snorting it to shooting in intramuscularly (IM), but she and her friend said it was even better if you shot it like heroin. We all sat cross-legged on her bedroom carpet, in a little circle. By then I was weaning myself off heroin; it had been weeks since I’d shot up, and I decided I wanted to IM the ketamine instead of using it intravenously. I shot it into my butt cheek. They shot it into their veins.

I watched them vanish.

Opal and our friend (who died the next winter of an overdose) sat hunched over, their needles dangling from their arms. They looked so dead that I checked their pulses before pulling the needles out, wiping their blood with napkins. The sight of them, so jarring, diluted my own high. Once they stirred, I said goodbye and left. That was the last time I used a needle. The last time I used ketamine. That was the last time I saw either of them

This is the moment in the story where I could say: I made it.

But that winter I got two DUIs in New York. I blew a .34 for my second one, high enough to die from alcohol poisoning. The police officer called another squad car because he didn’t believe the reading. I had passed my sobriety test.

But for my entire twenties, I was an active bulimic and alcoholic, with bouts of sobriety. I was also a firefighter and a nanny. It wasn’t until after my mom died by suicide that I reckoned with my drinking. Not for any reason except that it didn’t work anymore. My pain was always there, no matter what.

At 42 I am not sober. Sometimes I drink wine. Sometimes I take a sleeping pill. But I can honestly say my relationship with substances is good. I know that many people need sobriety, and I have spent years in sobriety, but the binary of sober/addict doesn’t serve me in my recovery. Being sober feels like too much pressure. Something to maintain. Right now I am technically sober, but I don’t like saying that, because it makes me want to drink. So, I don’t drink, for now.

I still relapse with my eating disorder. Not often, but sometimes. My life is wonderful in so many ways. I have everything I would have wanted, although things are precarious financially, I am single, and I have no children. All of these things are okay. I am mostly, almost always, present. Here.

Sometimes I think Peter’s the reason I’m alive. Because he didn’t survive. I wanted to do this for him, too. Become a writer. Live a whole life. Make space for those expansive realms here, in this one.

About a month ago, it was reported that Matthew Perry was in active addiction when he died.

Many people were angry that he’d written this entire memoir about sobriety and recovery when he was still struggling. But I get it. The world wants that recovery narrative. We all want to visualize ourselves climbing the mountain, getting to the top, and conquering our inner conflicts, demons, or addictions.

But I don’t think there’s a single mountain to be conquered, and this belief in conquering or triumphing over something “bad” can blind us to ourselves and ultimately keep us from acceptance and love.

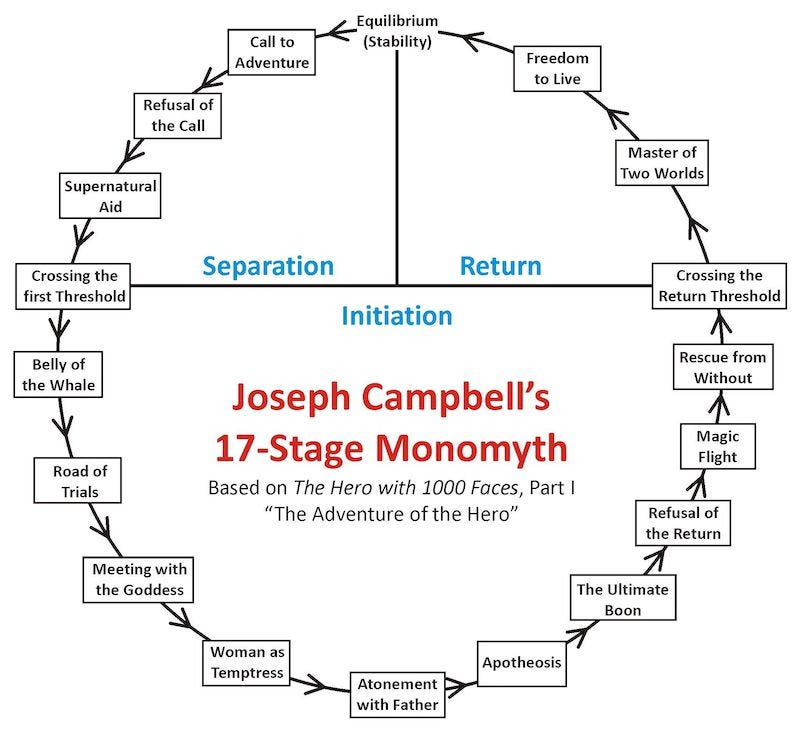

This narrative of climbing the mountain and conquering oneself has historical origins in many ancient stories. Joseph Campbell popularized the narrative as “the hero’s journey” but this structure permeates human history. Since the release of Campbell’s book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which broke down the structure into twelve parts, writers, artists, and self-help guides have refashioned it to fit their needs.

When I first began my eating disorder recovery, I was taught to see “recovery” as being totally free from disordered eating.

I imagined some future self who’d be at peace with their body and the world, and never feel conflicted about food. Unlike most addictions, once cannot recover from an eating disorder by quitting or staying away from their drugs or casinos or alcohol. We have to eat food. Every day. Several times a day. Because I framed recovery as an absolute, I kept relapsing. A lot. And I told people I was recovered when in actuality I was still actively bulimic.

Now I know that absolute recovery when it comes to eating disorders may be possible for some but is not something that’s possible for me, as far as I can tell. I haven’t ruled it out, but I’ve stopped picturing myself in the future, recovered.

Instead, I take it day by day. If I relapse, I know it’s a sign that something is out of balance and needs to be addressed. My bulimia pops up like a red flag, warning me to stop and pay attention. And you know what? I’m grateful for that. Grateful I can see and acknowledge it.

There is no mountaintop when it comes to my recovery. Yes— I have over a decade clean from IV drug use, but I did use opiates when I had surgeries. And I was okay. I survived. I threw away the pills when I didn’t need them anymore. Did I like the way they made me feel? Sure. But I know what’s on the other side if I don’t throw away the bottle. It’s better here.

And yes— I can have a single glass of wine. Although I don’t drink often. It’s when I want to drink that I know I shouldn’t. So I don’t.

Sometimes I feel in total alignment with food and eating and body image for several weeks or several months or a year; and then something happens and I am knocked out of alignment for a day or two, or a month or two.

My work resides in accepting myself during those times. In forgiving myself. When I loosen my grip and forgive, things improve. Until they’re fucked-up again. And so on.

Maybe there are a thousands mountains. Maybe there are none. Maybe there are simply days, and I am not a hero and will never be a hero. Maybe everything is chaos, and we make meaning however we can, in whichever way that works for us. Each of our lives is the same, and so different, all at once.

One of my favorite Buddhist teachers, Pema Chodron, relayed a story from her (very flawed) teacher, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. In essence, she says, we can compare our lives to walking in the ocean. When we’re hit by the first wave, it knocks us over. We have a choice to get up or not. If we get up, another wave inevitably comes and knocks us over again. The process repeats. As life unfolds, the waves never stop, but we learn how to dive into them, and some of the waves are smaller. We learn how to live with the waves. (read the story here).

I’m not telling you not to believe in the Hero’s Journey. I’m not telling you to do anything, or believe anything. What I am saying is: it may be much more complicated, and much more individual. What works for you works for you. What works for someone else works for someone else. Can we live with that?

In memoir and nonfiction, we can rethink the framing of a story as an arc of growth from one framework to another framework, instead of needing to arrive at a final, purely evolved destination. Once one has arrived, where is there to go?

Few things are ever totally resolved. But we can make peace with our own evolution, and we can pake peace with the mystery. Joy is there, in the mystery. Pain, too.

Lately I’ve been reminding myself: loving myself is not a destination. Simply wanting to love myself is an act of self love. What if I let myself rest there, in the wanting to love? What does it feel like?

It kind of feels like love.

Tell me: how are you loving yourself or not loving yourself? How do you perceive your journey? Your path through this life? And most of all: is there space for acceptance?

Paying subscribers, find the Zoom link for our Spacious Centering session below the paywall! If you’re planning on coming, please register via the link! And remember that you’ll be sent a recording and PDFs whether you come or not.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Gathering to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.